Table of Contents

The Australian art scene recently bid farewell to Allan Mitelman, a remarkable painter, printmaker, and educator whose contribution to the nation's abstract art is both significant and enduring. His passing prompted a wave of tributes, a testament to the deep respect he earned not only for his artistic achievements but also for his personal qualities.

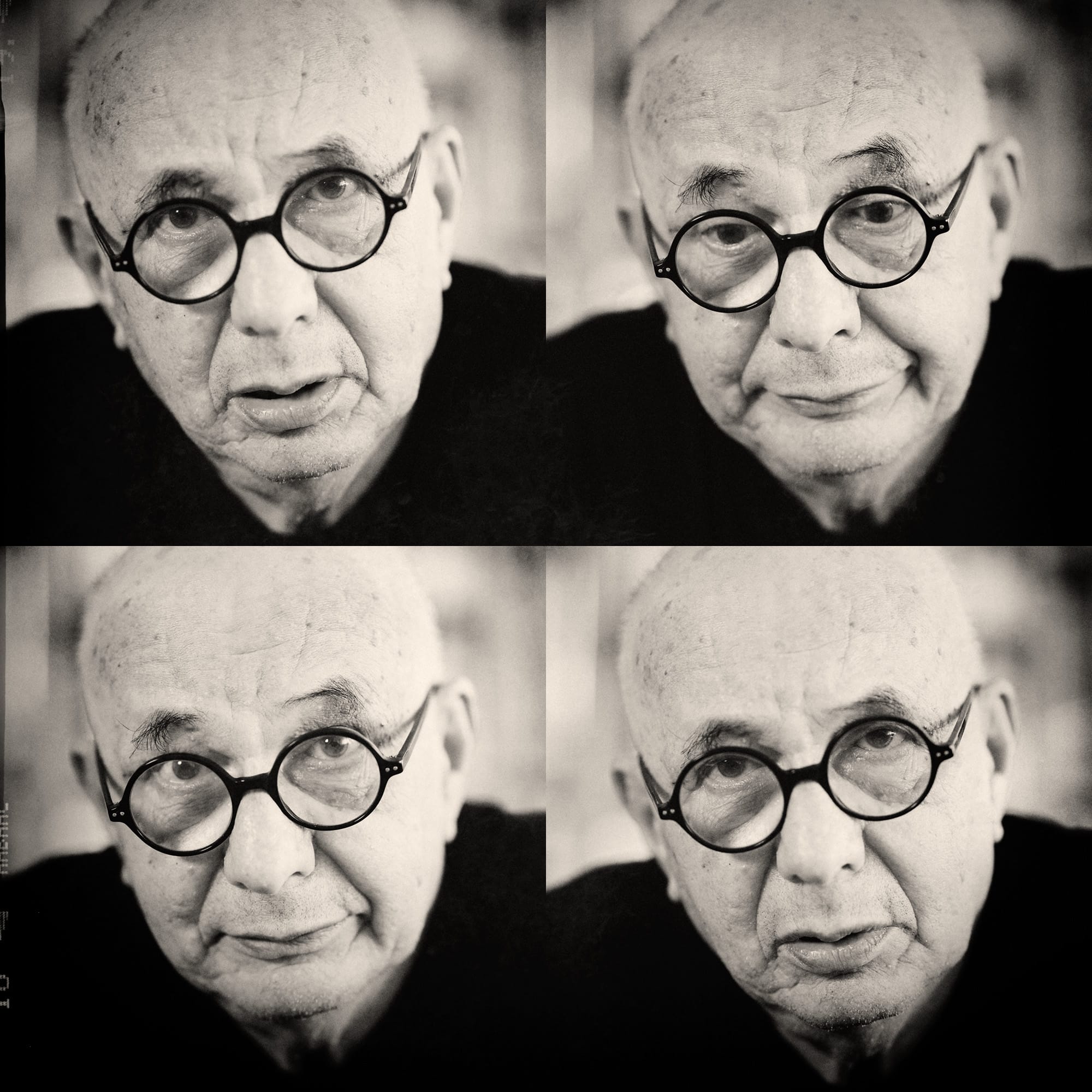

Mitelman stands as one of Australia's most important abstract artists, celebrated for his non-figurative style and his mastery across painting, drawing, and printmaking. He left behind a rich legacy, both through his prolific body of work and his influence on generations of students. Interestingly, for an artist of his stature, Mitelman was notably averse to self-promotion, often deflecting praise and insisting that his art should speak for itself. This humility, combined with a warmth, wit, and love for conversation, paints a portrait of a "larger than life figure" whose personality was as cherished as his art.

This story is an exploration of the interwoven threads of his life, his art, and his teaching. It's a journey to understand the evolution of his unique visual language, the influences that shaped him, his techniques, and his lasting impact on the Australian art world.

From Poland to Prahran: Forging an Artistic Identity (1946-1970)

Allan Mitelman's story begins in post-war Poland. Born in 1946, he was the son of Jewish refugees who had found sanctuary in Russia during World War II before making their way to Israel. In 1953, the family immigrated to Australia, seeking a new life as refugees when Mitelman was just a young boy. It's easy to imagine that these early experiences of displacement and starting anew profoundly influenced his worldview, though how directly they shaped his later abstract art is open to interpretation.

His artistic inclinations emerged early. As a schoolboy in Melbourne, Mitelman received invaluable early training from the Austrian-born sculptor Karl Duldig, spending Saturdays assisting him. This mentorship likely played a crucial role in solidifying his path toward the visual arts. After school, he initially explored architecture for a year, a discipline that, with its emphasis on structure and space, may have subtly informed his later compositions. Ultimately, his passion for art prevailed, and he committed to it fully.

Mitelman enrolled at the Prahran College of Advanced Education, where he studied from 1965 to 1968. This was an exciting time for the Melbourne art scene and for Prahran College itself, which was rapidly becoming an important center for artistic training, particularly with the establishment of its photography program. Driven to deepen his skills, especially in printmaking, Mitelman traveled overseas between 1969 and 1970. A pivotal moment during this period was his brief but intensive study of etching under the renowned Stanley William Hayter at the legendary Atelier 17 in Paris. Hayter's workshop was a melting pot of experimental printmaking techniques, and this exposure undoubtedly expanded Mitelman's technical abilities and connected him to the international avant-garde. Upon his return to Melbourne in 1970, he continued his printmaking studies at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT).

Mitelman's journey—from a refugee child arriving in Australia in 1953 to an artist exhibiting internationally less than two decades later—is truly remarkable. It speaks volumes about his innate talent and unwavering dedication, as well as the nurturing environment provided by Melbourne's art education institutions during that time. His diverse early experiences – sculpture with Duldig, his brief foray into architecture, the comprehensive art training at Prahran, specialised printmaking at RMIT, and the cutting-edge techniques he encountered at Atelier 17 – formed a rich and varied foundation for his career.

Recognition arrived quickly. In 1972, Mitelman's work was included in the prestigious "Australian Prints" exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in London, placing him alongside established giants like Arthur Boyd, Fred Williams, and Martin Sharp. This early inclusion in such a significant international showcase marked him as a rising star. Further solidifying his growing reputation, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York acquired an etching and a lithograph by Mitelman in the early 1970s. This acquisition by one of the world's leading modern art institutions provided crucial international validation early in his career, setting him apart and signaling that his artistic vision resonated far beyond Australia.

The Substance of Surface: Mitelman's Artistic Language

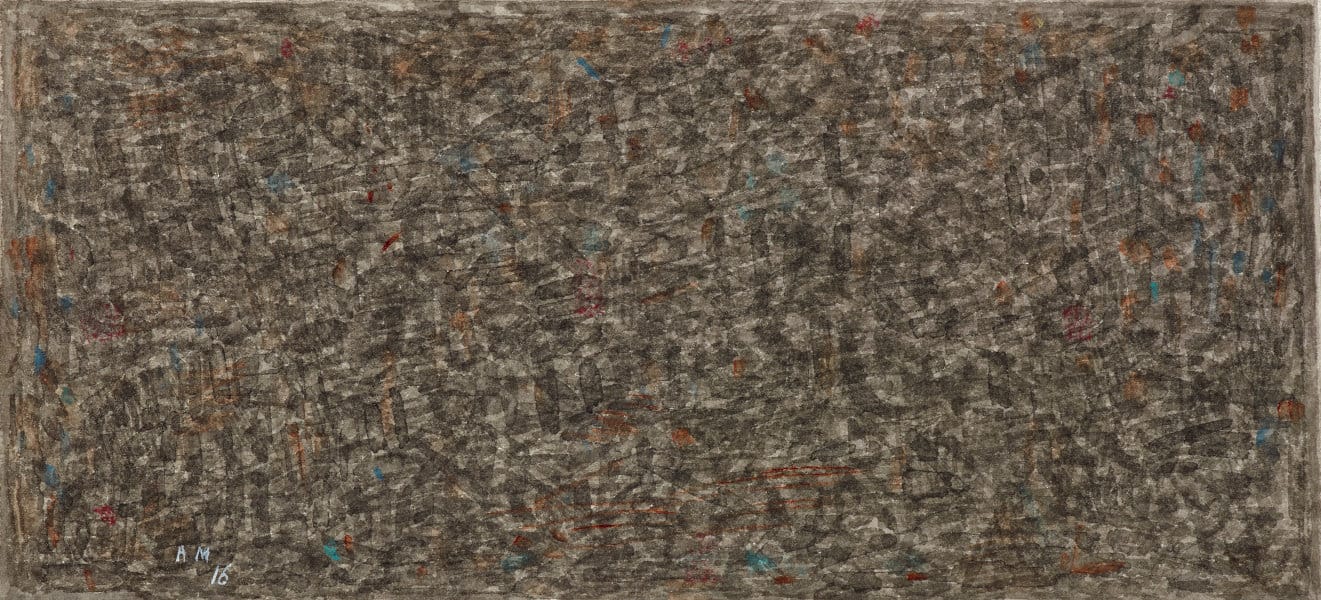

Throughout his long and productive career, Allan Mitelman remained steadfastly committed to abstraction. His work is consistently non-figurative, often described as minimalist, though this term doesn't quite capture its nuance. As the National Gallery of Victoria noted, he is "one of Australia's foremost abstract artists who holds an important place in the history of abstraction in this country". His focus was less on storytelling or depicting the world and more on the inherent qualities of the artwork itself: the subtle variations of surface, the richness of texture, and the delicate harmonies of color and tone.

Mitelman moved effortlessly between painting, drawing, and printmaking, demonstrating exceptional skill in each. His paintings, often created with oil or acrylic paint on canvas or board, are known for their textured surfaces. These textures arise from an intuitive process of layering paint and manipulating the medium, frequently using a palette knife to build up or scrape back the surface, creating fields of visual interest.

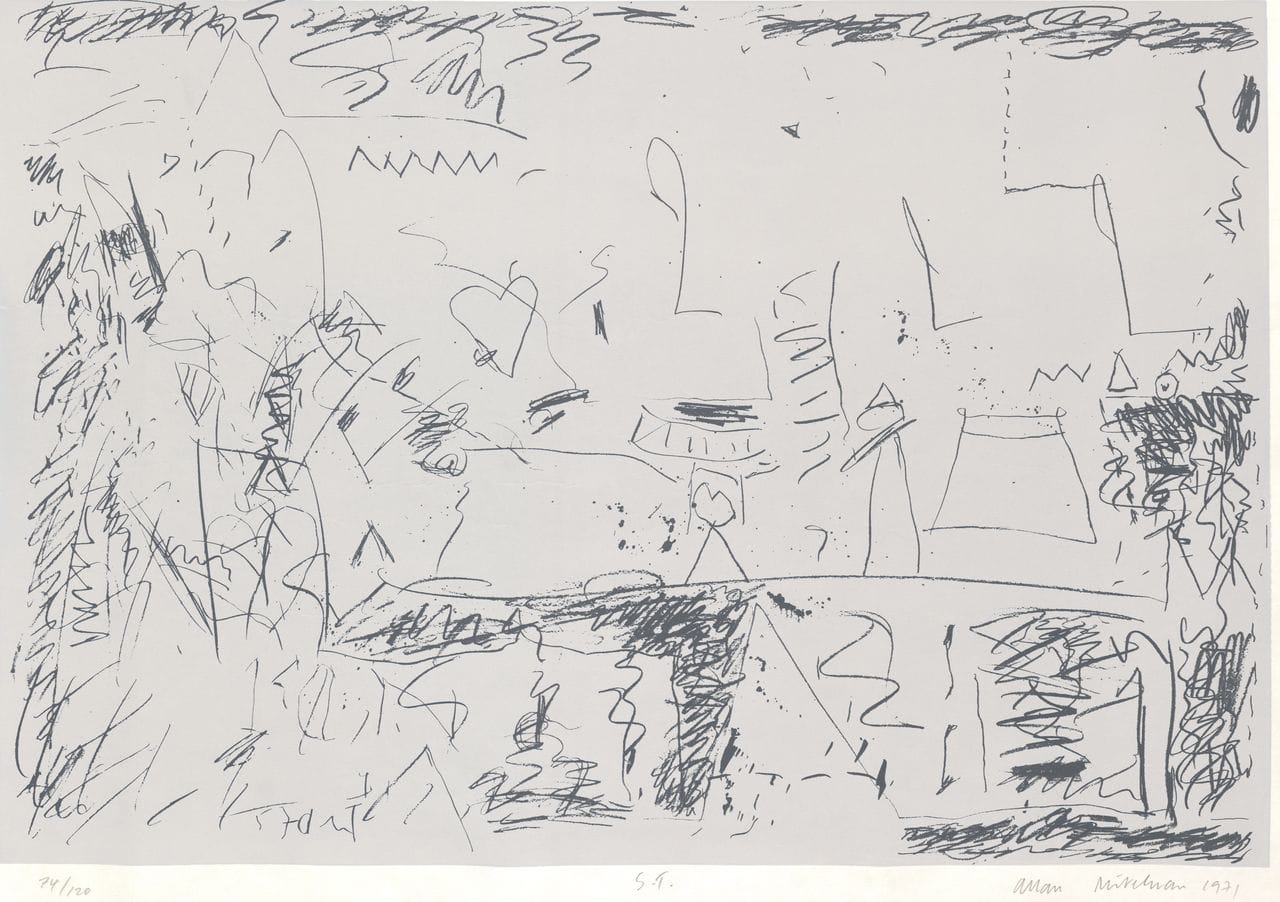

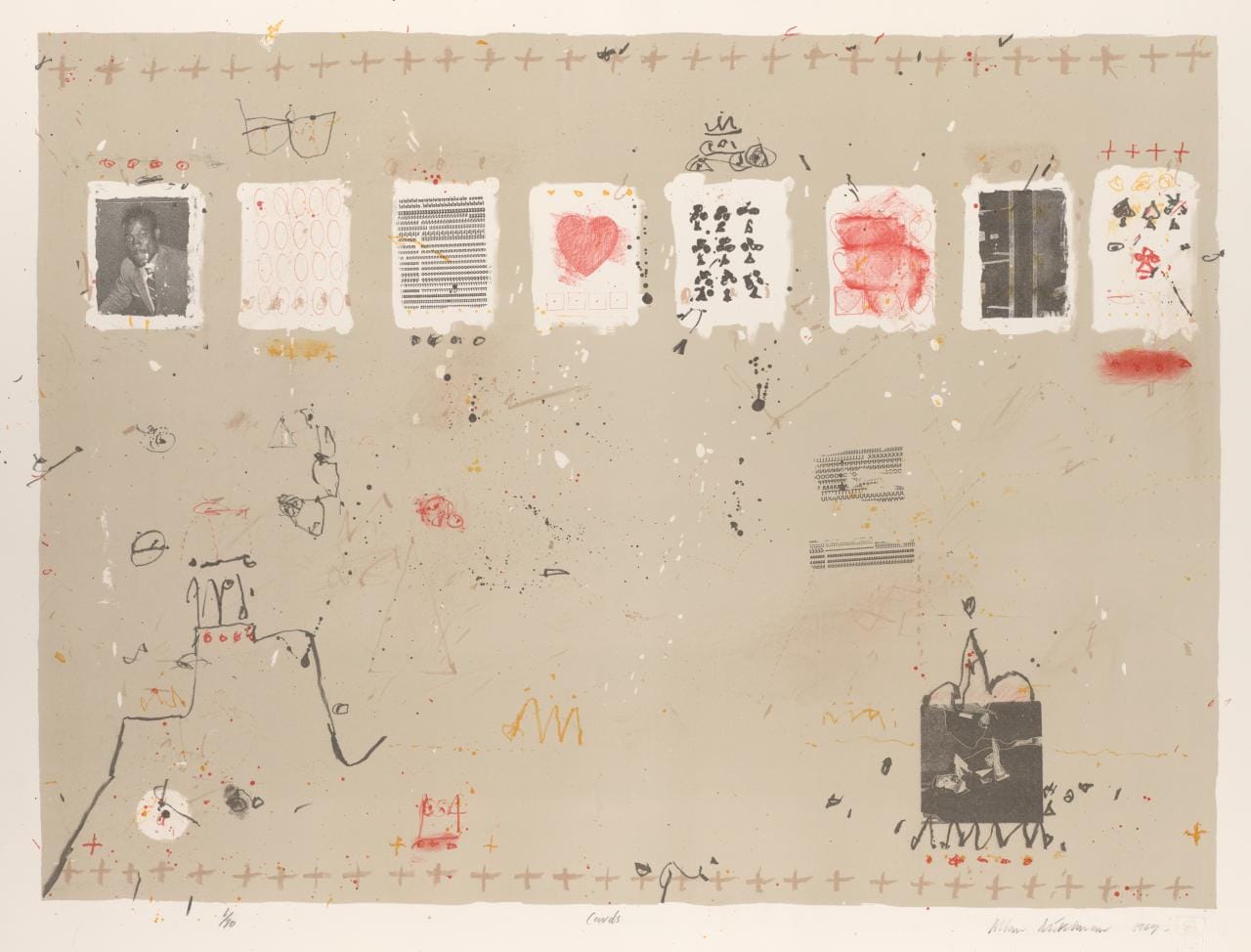

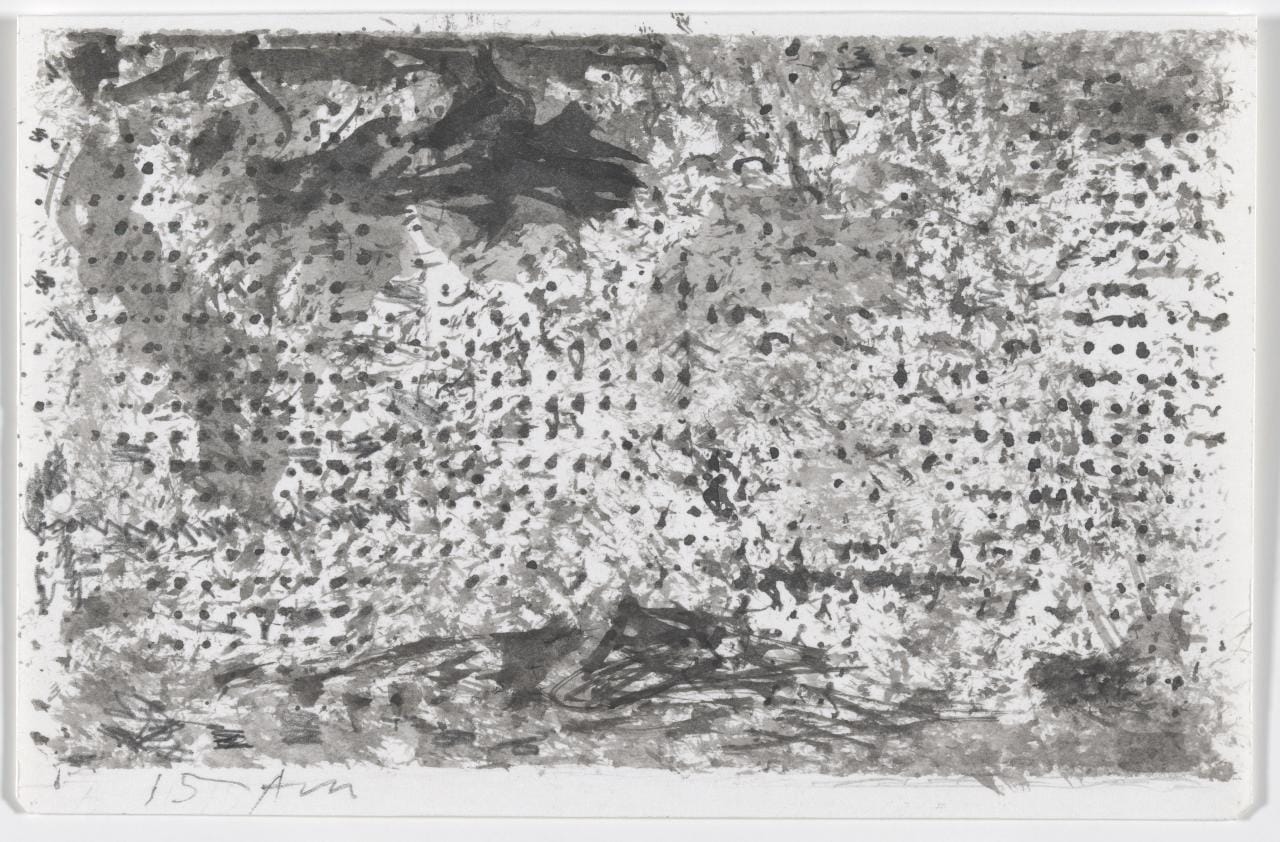

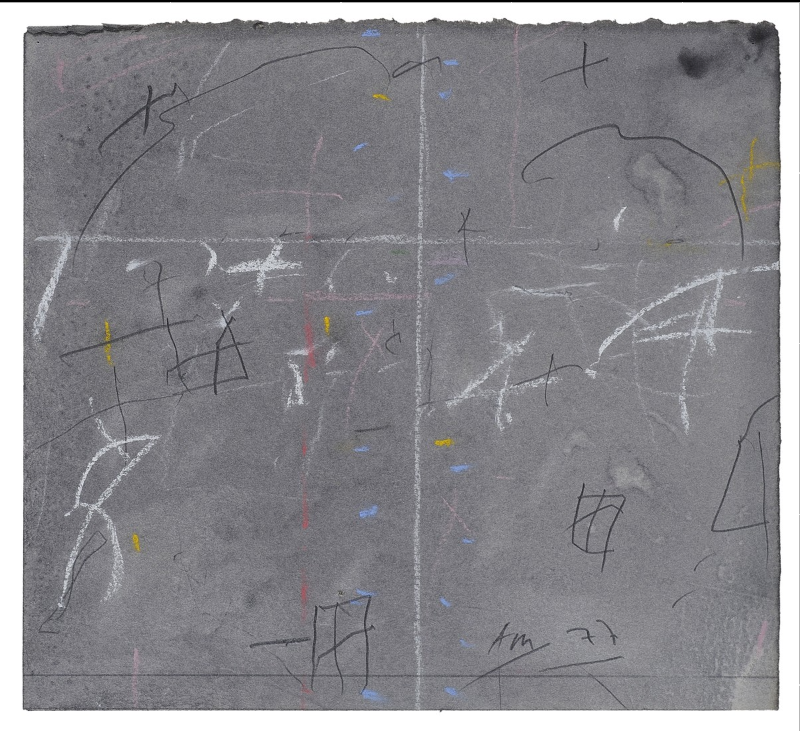

Works on paper, however, formed a central and continuous thread throughout his artistic journey, from his earliest explorations to his final creations. He employed a wide range of media and techniques, showcasing remarkable dexterity. His drawings might involve pencil, often combined with colored crayon or watercolor, sometimes incorporating techniques like scratching out to reveal underlying layers. Pastels, gouache, ink, and charcoal also feature prominently, often combined in mixed-media works. His printmaking embraced lithography, etching, screen-printing, and monotype. He particularly relished the directness of drawing on the lithographic stone, a process that for him intimately connected hand, mind, and material.

Mitelman's works vary significantly in scale. Alongside large canvases, he produced many small, intimate works on paper, sometimes described as "ephemeral and fugitive," revealing an experimental side. These smaller pieces offer a contrast to more elaborate drawings that often reached a size comparable to paintings. Regardless of size, a striking characteristic of his body of work is the frequent use of the title "Untitled". While occasional evocative titles appear, the prevalence of "Untitled" deliberately steers the viewer away from seeking narrative meaning or external references. Instead, it encourages a direct engagement with the work's formal and material qualities – its lines, colors, textures, and the interplay between them. This approach aligns perfectly with the essence of his art, which invites contemplation and the "sensual enjoyment of the concrete materiality of the work itself".

Conceptually, Mitelman's abstraction seems rooted in the very act of creation. Comparisons have been drawn to the American artist Cy Twombly, known for his calligraphic gestures, and the English painter Roger Hilton, whose abstraction often retained a connection to landscape or the figure, and whose work Mitelman admired. There's also a noted interest in the uninhibited quality of children's early mark-making and an analogy drawn between the rhythmic quality of his compositions and musical scores. These connections suggest an art grounded in fundamental human impulses – gesture, rhythm, sensory experience – refined through a sophisticated understanding of materials and processes. His minimalism, therefore, seems less about stark emptiness and more about distilling the essence of the artistic act and the inherent beauty of the materials he used. The deep, lifelong engagement with the physical processes of painting, drawing, and printmaking underscores that his abstraction was not detached or purely intellectual, but viscerally connected to the substance of surface.

In Conversation: Influences, Contemporaries, and Context

Allan Mitelman's artistic practice developed within a rich network of influences, peer interactions, and institutional connections, both locally and internationally. His early mentor, the sculptor Karl Duldig, provided crucial encouragement. Later, his experience with S.W. Hayter in Paris connected him directly to the forefront of international printmaking. The comparisons drawn by critics to Cy Twombly and Roger Hilton place his mature work within a broader dialogue of post-war abstraction that emphasised gesture, texture, and surface nuance. His personal admiration for Hilton, evidenced by his owning a drawing by the English artist, further solidifies this connection.

Within Australia, Mitelman was deeply embedded in the Melbourne art world, particularly during the vibrant decades of the 1970s and 1980s. His early inclusion in the 1972 V&A exhibition placed him alongside established figures like Fred Williams and Arthur Boyd, as well as the distinctive pop voice of Martin Sharp. His long teaching career at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) fostered close relationships with colleagues. He shared a strong bond with Graham Fransella, who initially worked as a technician before becoming a successful artist himself. Other notable VCA colleagues during his tenure included the influential printmaker Bea Maddock and John Scurry, a fellow Prahran alumnus who eventually succeeded him as Head of Printmaking. The VCA environment also brought him into contact with prominent artists like Gareth Sansom and visiting curators like Robert Lindsay. His circle included other significant Melbourne figures associated with the VCA or the broader abstract scene, such as Paul Partos, Jenny Watson, and John Nixon.

His engagement with the printmaking community extended beyond teaching. He participated in key surveys like "Twelve Australian Lithographers" at the NGV in 1975 and worked extensively with the Australian Print Workshop (APW), collaborating with skilled printers like Kim Westcott and Ian Parry. This sustained involvement highlights the collaborative aspect inherent in much printmaking and Mitelman's dedication to exploring the medium's technical possibilities, contributing to the sophistication and experimental nature of his printed oeuvre.

Mitelman maintained a prolific exhibition schedule from 1969 onwards. He showed regularly with influential commercial galleries across Australia. In Melbourne, his work was seen at Crossley Gallery, Powell Street Gallery, Pinacotheca, 312 Lennox Street, and Deutscher Brunswick Street. Sydney representation included Macquarie Galleries, Garry Anderson Gallery, and Ray Hughes Gallery, while in Perth he exhibited with Galerie Düsseldorf. In later years, he developed a particularly strong and enduring relationship with Charles Nodrum Gallery in Richmond, Melbourne, a gallery known for its focus on Australian abstraction, particularly from the 1960s onwards. He also exhibited with MARS Gallery in Windsor, Melbourne. This network of gallery representation ensured his work was consistently visible to collectors and the public across the country.

Mitelman successfully navigated both local and international art currents. While deeply connected to the Melbourne scene through teaching and exhibiting, his artistic language resonated with international abstract trends, and his early overseas recognition set the stage for a career that consistently engaged with a world beyond Australia's shores.

The Educator's Mark: Teaching and Mentorship

Beyond his own prolific artistic practice, Allan Mitelman made a significant contribution to Australian art through his dedicated career as an educator. His teaching journey began in 1972 with a lecturing position at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) School. Around the same time, he commenced teaching printmaking at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) in Melbourne, an institution where he would spend a substantial part of his career.

At the VCA, Mitelman became Head of the Printmaking department, a role he held for approximately two decades, from the early 1970s until 1992. His leadership coincided with a period when printmaking was gaining increased prominence and sophistication within Australian art schools. His tenure as Head concluded in 1992 following the merger of Prahran College with the VCA, which led to a restructuring where John Scurry, formerly Head of Printmaking at Prahran and a fellow Prahran alumnus with Mitelman, took charge of the newly expanded department.

He famously quipped that he "pretended to teach", a typically self-deprecating remark that perhaps hinted at a pedagogical style favoring student-led discovery over rigid instruction. Descriptions from colleagues and photographic evidence portray him as a "witty, voluble" presence in the staff room, capable of hamming it up, but fundamentally kind-hearted and gentle. This combination of humor, warmth, and artistic authority likely created an engaging and supportive learning environment.

The impact of his teaching is undeniable, contributing significantly to his deep legacy as both an artist and teacher. Several of his former students went on to achieve significant recognition, including Kim Westcott and John Dahlsen. Most notably, his influence is cemented by the fact that former students chose him as a subject for Australia's most prestigious portrait competition, the Archibald Prize. Lewis Miller's compelling portrait of Mitelman won the Archibald Prize in 1998, bringing national attention to both the painter and his subject. Miller had submitted portraits of Mitelman, whom he described as a great friend and an "extremely nice person". That multiple students felt compelled to capture his likeness for such a high-profile prize speaks volumes about the profound impact Mitelman had, extending far beyond technical instruction to encompass mentorship and genuine human connection.

Making a Mark: Recognition and Key Works

Allan Mitelman's contribution to Australian art was consistently recognised throughout his career through numerous awards, significant survey exhibitions, and the acquisition of his work by major public collections both nationally and internationally. His accolades spanned several decades and acknowledged his prowess, particularly in printmaking early on, but also later in painting and drawing. Key awards include the Geelong Print Prize (1970), the Henri Worland Print Prize (Warrnambool, 1972), the Corio Art Prize (1974), the Wollongong Art Purchase Prize (1976), the Fremantle Arts Centre Print Prize (1976), and the Bathurst Art Award (1977). He received grants from the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council in 1973 and a Fellowship in 1989. Later significant awards were the prestigious Sulman Prize from the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2004 and the James Farrell Self Portrait Award in 2007.

His exhibition history is extensive, including numerous solo shows held almost annually since 1969 in leading commercial galleries across Australia. Two major survey exhibitions provided comprehensive overviews of his career: "Allan Mitelman, After-images: A survey of works from 1970-1995," held at the Heide Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne and the Drill Hall Gallery (ANU) in Canberra in 1995; and the landmark "Allan Mitelman: Works on Paper 1967-2004," curated by Elizabeth Cross for the National Gallery of Victoria in 2004, which subsequently toured to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. He was also featured in significant curated group exhibitions both in Australia and overseas, including the aforementioned "Australian Prints" at the V&A (1972), the Ninth International Print Biennale in Tokyo (1974), "Twelve Australian Lithographers" (NGV, 1975), "Prints and Australia: Pre-settlement to Present" (NGA, 1989), "Reference Points" (QAG, 1992), "Silent Objects: Non-Objective Art from Melbourne" (Centre for Contemporary Art, Hamilton, NZ, 1994), and "Southern Reflections, 10 Australian Artists" (Stockholm, Sweden, 1998).

The enduring significance of Mitelman's work is further confirmed by its presence in numerous major public collections. In Australia, his art is held by the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), Heide Museum of Modern Art, the Baillieu Library Print Collection at the University of Melbourne, Geelong Gallery, Warrnambool Art Gallery, Wollongong Art Gallery, Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, and Fremantle Arts Centre, among others. Internationally, his work has been acquired by prestigious institutions including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the British Museum in London, the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in London, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, Auckland Art Gallery, and Christchurch Art Gallery. This extensive list of institutional acquisitions, spanning his entire career and including top-tier national and international museums, unequivocally confirms his status as an artist of major importance.

Conclusion: An Enduring Resonance

Allan Mitelman leaves behind a significant and multifaceted legacy. He was, first and foremost, a distinctive and influential voice within Australian abstract art, pursuing a singular vision for more than five decades. His mastery encompassed painting, drawing, and particularly printmaking, where his innovative approach and deep engagement with materials produced an exceptional body of work. His consistent focus on the nuances of surface, the subtleties of texture, and the evocative potential of non-figurative marks carved out a unique space within the broader landscape of contemporary art. His work offers a counterpoint to more overt or narrative-driven styles, inviting viewers into a quieter, more contemplative engagement with the fundamental elements of visual experience.

His contribution extends beyond his own creations. As a long-serving educator and Head of Printmaking at the VCA, he played a crucial role in shaping a generation of artists, fostering their talents within a supportive, if characteristically understated, environment. The respect and affection he garnered are evident in the tributes following his passing and the notable portraits created by his former students. Remembered by friends and colleagues for his wit, warmth, and intellectual curiosity, Mitelman navigated the art world with a characteristic aversion to hype, preferring to let the work speak for itself. He is survived by his children, Matisse and Celeste, and grandchildren.

The loss of Allan Mitelman marks the departure of a major figure from the Australian art community. Yet, his legacy endures through the substantial body of work held in public and private collections worldwide, and through the ongoing influence of his teaching. His art, with its quiet intensity and profound respect for material, continues to offer a space for slow looking, sensory enjoyment, and thoughtful contemplation, ensuring its resonance for years to come.