Table of Contents

Joan Mitchell’s journey was one of fierce independence, unwavering dedication to her craft, and a unique ability to translate the sensations of the natural world into the language of abstract gesture. She navigated the complex currents of the post-war art world on her own terms, creating a body of work that resonates with emotional honesty and visual power. The upcoming exhibition at Tate Modern offers a crucial opportunity to experience the full scope of her achievement – from the intense canvases forged in the crucible of New York Abstract Impressionism to the luminous, expansive landscapes of feeling painted under the French sky. It promises to be a powerful reminder of an artist who painted not just what she saw, but the very pulse of life itself.

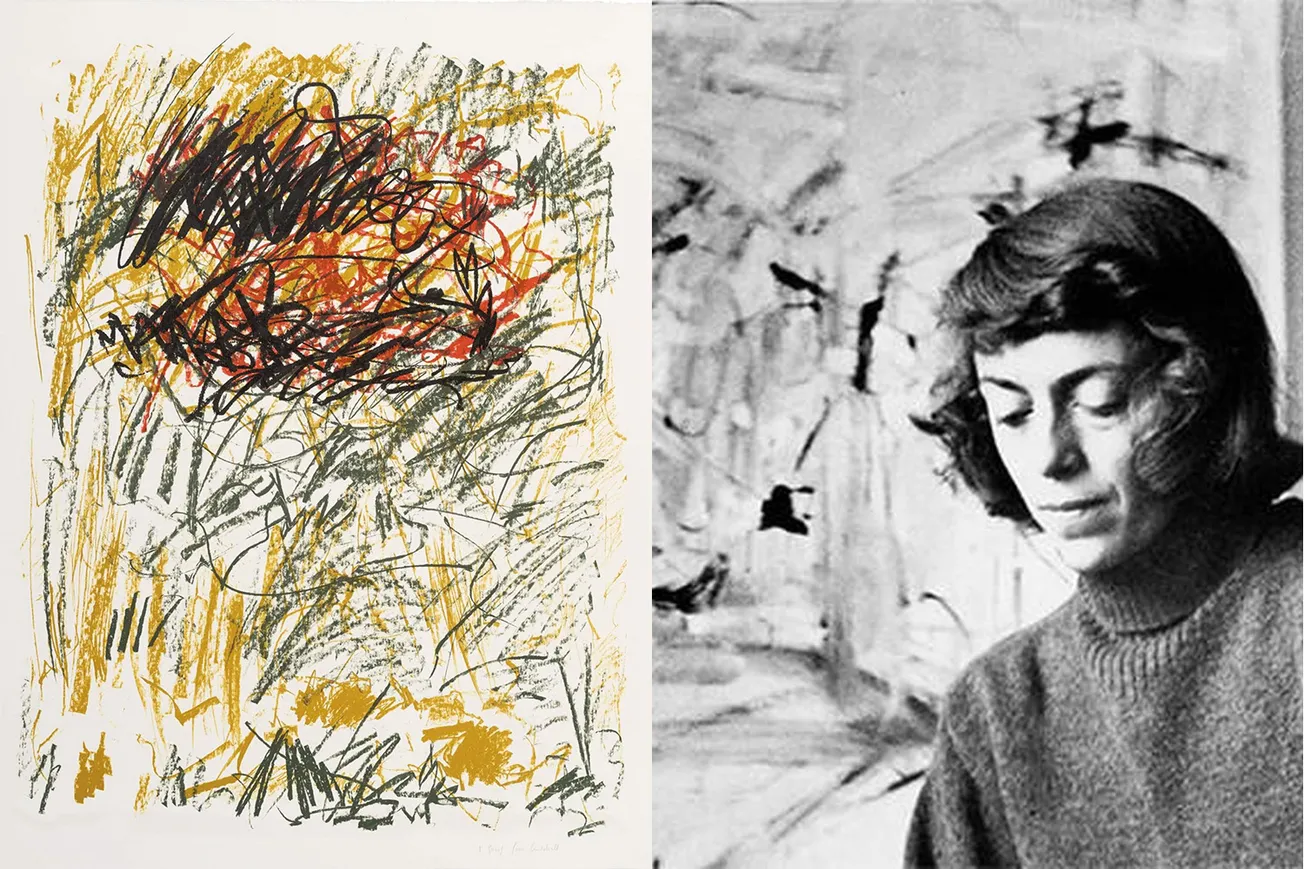

Unusual for a New York School Abstract Impressionist painter (with the exception of Helen Frankenthaler), Mitchell’s life began not in the gritty lofts of downtown New York, but in the affluent surroundings of Chicago in 1925. Her upbringing was steeped in culture and competition. Her father, James Herbert Mitchell, was a successful doctor, and her mother, Marion Strobel, was a published poet, editor of Poetry magazine, and co-conspirator in the city's literary scene. This environment fostered both intellectual curiosity and a certain pressure to achieve. Young Joan was a gifted athlete – a competitive figure skater – alongside demonstrating early artistic talent, taking classes at the Art Institute of Chicago from a young age. The blend of physical discipline and creative expression would arguably inform the dynamic, gestural nature of her later work. Her education continued at Smith College before she returned to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, earning both a BFA and an MFA. A travel fellowship then took her to France in 1948-49, an experience that planted the seeds for her lifelong connection to the country.

Returning from Europe, Mitchell didn't head back to Chicago but plunged into the heart of the American post-war art revolution: New York City. By the early 1950s, she was immersed in the downtown scene, a regular at the Cedar Tavern and the Artists' Club – the legendary haunts where Abstract Expressionism was being forged in fiery debate and copious amounts of alcohol. She was part of the landmark "Ninth Street Show" in 1951, curated by Leo Castelli, which solidified the arrival of this new, radical abstraction.

Mitchell found herself associated with the group often retrospectively labelled the "9th Street Women," including artists like Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Grace Hartigan, and Helen Frankenthaler. While sharing geography and a commitment to abstraction, Mitchell fiercely resisted being defined solely by her gender within the movement. She was younger than Krasner and Elaine de Kooning, and while friendly with some, she maintained a prickly independence and a competitive drive that matched any of her male peers, like Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Philip Guston. She wasn't interested in being a "woman artist"; she was a painter, period, demanding to be judged on the same terms as the men who dominated the narrative. Her work, while sharing the gestural energy of Abstract Expressionism, always retained a distinct grounding in landscape and feeling, setting it apart from the pure psychic automatism or colour field explorations of some contemporaries.

Mitchell's personal life was as intense and complex as her art. A brief early marriage to Barney Rosset, the adventurous publisher of Grove Press, ended, but her most significant relationship was a long, passionate, and often tumultuous partnership with the French-Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle, himself a major figure in abstraction. Their connection, lasting nearly 25 years, was marked by deep artistic respect, shared sensibilities, fiery arguments, and periods of separation, fuelled partly by their mutual dedication to their work and independent lives.

The pull of France, first felt during her post-graduate fellowship, eventually became permanent. Starting in the late 1950s, she divided her time between New York and France, finally settling there full-time in 1968. She purchased a property in Vétheuil, a village overlooking the Seine valley northwest of Paris, notable for being where Claude Monet had lived and worked decades earlier. This move wasn't a retreat, but a deepening immersion. The light, the colours, the specific flora of the French countryside became central catalysts for her work. While never painting en plein air in the Impressionist manner, the memory and sensation of the landscape – its changing seasons, its textures, its atmospheric shifts – saturated her canvases.

Her style evolved significantly during this period. While the energetic brushwork remained, her compositions often became more expansive. She embraced large-scale formats, frequently working in diptychs and triptychs that allowed her to explore panoramic breadth and complex internal rhythms. Passages of dense, vibrant colour might collide with areas of sparer canvas, creating dynamic tensions between form and void, energy and calm. References to specific places, times, or feelings became more explicit in her titles – La Grande Vallée, Sunflowers, Champs – grounding the abstraction in tangible experience. Mitchell’s work became a powerful translation of external nature through the filter of internal emotion and memory. Even as she battled physical ailments later in life, including severe hip dysplasia and oral cancer, her dedication to painting remained absolute, her output astonishingly vital until her death in Paris in 1992.

Three Works:

- Hemlock (1956): Created during her potent New York period, Hemlock exemplifies Mitchell's early Abstract Expressionist power fused with personal memory. The title refers to a hemlock tree on her mother's property, linking the abstract composition to a specific, emotionally charged natural form. The canvas surges with energy – slashing black lines intertwine with bursts of white, green, and touches of ochre and blue. It’s dense, almost claustrophobic in its all-over intensity, reflecting the muscularity often associated with the movement. Yet, unlike some purely non-objective Abstract Expressionist work, there's a palpable sense of organic structure, a tangled, thorny vitality that feels drawn from the natural world, albeit transformed into pure painterly gesture. The work conveys a feeling of contained, slightly menacing power, the darkness of the hemlock rendered as both form and feeling. It’s a quintessential statement of her early ability to load abstraction with visceral, remembered experience.

Two Sunflowers (1980): This monumental diptych, painted a decade before her final sunflower series, stands as a powerful testament to Mitchell's mature Vétheuil period and her ongoing dialogue with both the natural world and art history, particularly Van Gogh. Rather than the overtly elegiac tone that might characterise some of her latest works, Two Sunflowers radiates a fierce, almost defiant vitality. Executed on a vast scale across two canvases, the work engulfs the viewer in an explosion of colour and gesture. Thick strokes of cadmium yellow, brilliant orange, and verdant green tangle and clash, forming the radiant heads and sturdy stalks of the titular flowers. These aren't delicate botanical specimens; they are forces of nature rendered with raw energy. Surrounding blues, whites, and violets suggest the shimmering atmosphere of the French countryside – perhaps sky, perhaps the cool space against which the sunflowers blaze. The "two-ness" is compelling: are they companions, rivals, or two aspects of the same life force? Mitchell doesn't offer easy answers, instead using the duality to create complex rhythms and tensions across the diptych's expanse. The work brilliantly balances abstract expressionist energy with the perceived structure and feeling of the sunflowers, capturing their assertive presence and the intense sensation of light and life they embody. It's a prime example of Mitchell translating a specific natural motif into her deeply personal, emotionally charged abstract language, demonstrating her mastery of colour and large-scale composition during her incredibly fertile French period.

Girolata Triptych (1963): This work marks a transition, reflecting her increasing time in Europe and her burgeoning interest in multi-panel formats. Inspired by the light and landscape of Corsica, the triptych format allows Mitchell to create a panoramic sweep, a narrative progression across the three canvases. Compared to Hemlock, there's a greater sense of air and light. While still intensely gestural, the colours – brilliant blues, yellows, greens, and whites – evoke the sun-drenched Mediterranean environment. The brushstrokes feel less interwoven and more like distinct bursts or flows of colour interacting across the panels. There's a dialogue between dense areas and more open spaces, creating rhythms of expansion and contraction. The triptych structure allows her to explore variations on a theme, suggesting changing light or shifting perspectives within a single, expansive experience. It shows Mitchell harnessing the energy of Abstract Expressionism, but channelling it into compositions with a clearer, albeit still abstract, relationship to place and atmosphere.