Table of Contents

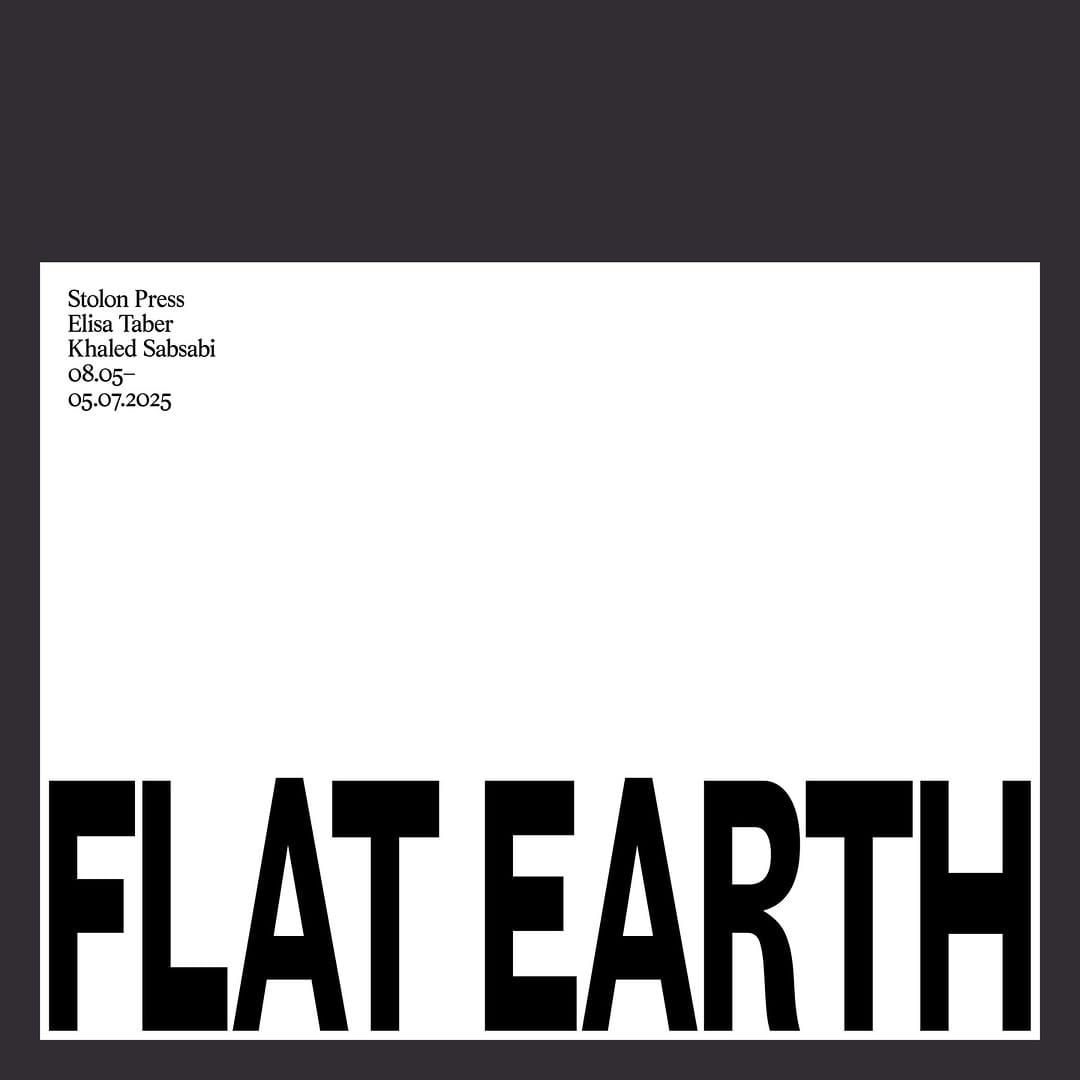

In a sudden(ish) turn of events, Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) has announced the reinstatement of Khaled Sabsabi’s exhibition, Stolon Press: Flat Earth, originally postponed amid controversy. The exhibition, now opening on 29 May, offers viewers a profound exploration of cultural identity, memory, and spirituality through unique calligraphic artworks crafted using Lebanese coffee.

Khaled Sabsabi’s work emerges from deeply personal reflections on his childhood experiences during the Lebanese civil war, bringing forward intimate, spiritual imagery that bridges his past and present. Employing Lebanese coffee as his medium—a culturally symbolic material—Sabsabi intertwines tradition and contemporary practice, drawing viewers into a meditative dialogue about war, displacement, and resilience.

The postponement of Stolon Press: Flat Earth initially drew speculation linking the decision to external pressures and political sensitivities surrounding Sabsabi’s advocacy work. Notably, Sabsabi participated in the widely publicised 2022 boycott of the Sydney Festival, responding to sponsorship by the Israeli embassy. The boycott was part of a global conversation around art’s role in political expression and resistance, mirroring recent international dialogues around artistic freedoms—such as the controversies involving the postponement of exhibitions by Palestinian artists in Germany and debates over political neutrality in museum practices globally.

Sabsabi, however, has consistently and vigorously denied accusations of promoting antisemitism or extremism. The reinstatement of his exhibition is widely celebrated within the Australian art community as an affirmation of the essential freedoms of artistic expression and open dialogue.

In a statement, Monash University emphasised the importance of fostering spaces for critical reflection, stating that their role as an educational institution is to engage deeply with complex cultural conversations, not shy away from them. This decision has resonated positively among artists, educators, and students, highlighting the university’s commitment to artistic diversity and intellectual integrity.

Similar incidents have seen museums navigating the tensions between external political pressures and the need to uphold artistic freedom. Notably, controversies such as the Whitney Museum’s debates over ethically charged artwork or recent cancellations of exhibitions due to political sensitivities underscore the international relevance of Monash’s decision.

For educators and students, Sabsabi’s exhibition provides a compelling case study in how art intersects with political and social discourse. It serves as a powerful example of the significance of supporting diverse voices within cultural institutions, ensuring that educational spaces remain vibrant arenas for critical engagement.

Monash’s reversal is more than a single exhibition; it signifies a reaffirmation of art’s critical role in society, reminding us all of the ongoing need to protect and celebrate creative freedom.